Three Principles of (African) Business

As an organization that invests, buys, and builds with a long term horizon, Akili’s strategy is driven by strong theses and convictions based on macro trends economically, politically, and demographically, but also micro trends on business and consumer behaviors. As a result, we must be sensitive to trends we see emerging, and learn lessons that we can apply broadly to our business and investment activities, which help shape and reshape our strategies. Being diversified in our theses and activities, we often have observations across activities that we like to bubble up that shape how we see things.

The following are 3 principles we’ve run into again and again that shape our view of doing business, and particularly doing it in Africa.

Trailing Indicators

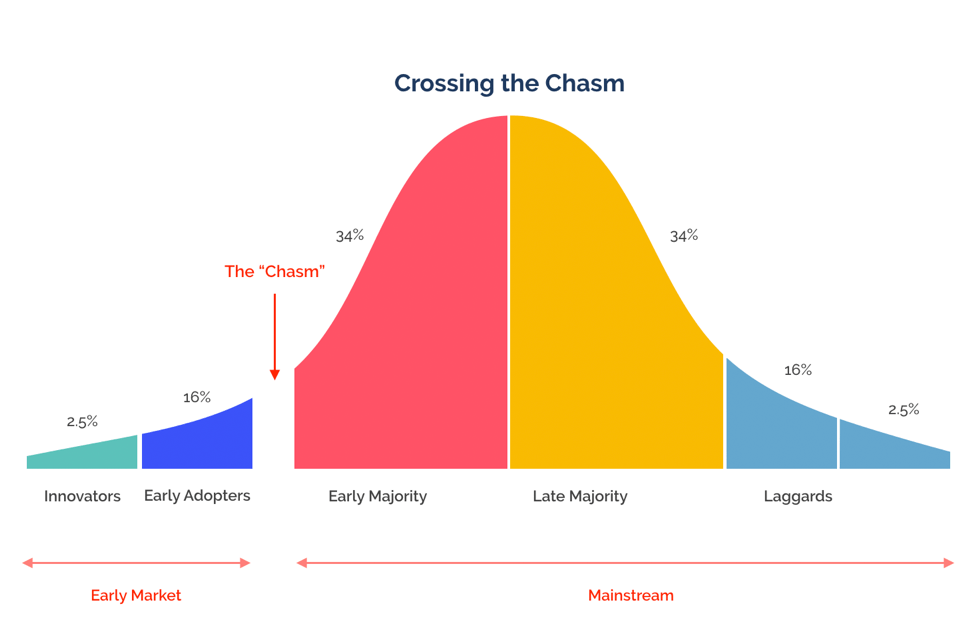

In his book, “Crossing the Chasm”, Geoffrey Moore illustrates the famous technology lifecycle adoption curve. The curve indicates that new and early innovations tend to attract “early adopters” first. A small and committed band of users of a product who are willing to put up with bugs and limited features to try something new and exciting, and provide feedback. These early adopters are those who are ready to embrace risk, who want the newest things, and don’t mind when things don’t work. As these early adopters use the product, they provide invaluable feedback that drives iteration cycles that allow the product to be improved, until more mainstream users are ready to engage with it. As the product matures more mainstream, risk averse, and technologically less savvy users adopt it. At the end of the adoption curve comes a long tail of laggards (i.e. grandparents on Facebook :). In between the early adopters and more mainstream users, there is a “chasm” that a product must cross (hence the title of the book) to achieve widespread adoption and scale, since the majority of users reside on the mainstream side of the chasm.

In the investment community, there is a similar lifecycle adoption curve for new innovations in the world of investing. In the volatile world of crypto for example, the early adopters were mostly from the highly technical specialties of cryptography and computer security. Later, institutional and ultimately retail investors joined the party, chasing (seemingly impossible) short term returns, and pumping massive amounts of liquidity into the system. Venture capital might seem like a more tame and conservative example than crypto, but not too long ago it was viewed in much the same way, as highly radical and highly risky. At this point, the type of LPs that finance venture funds: pension funds, retirement funds, university endowments, public and private foundations, see venture as a typical part of a diversified portfolio. But not long ago their money managers would have viewed venture in much the same way as they viewed crypto in its first few years.

Several months ago I was told by a friend about the Central New York Community Foundation, where he sits on the board. A community foundation is essentially a non profit organization that acts as a sponsor for small individual donors who want to engage in philanthropic giving without setting up their own foundations or infrastructure. The community foundation takes in funds from individual donors, manages it in one large pool, and makes philanthropic donations based on its area of giving, or sometimes on the recommendations of the donors. The Central New York Community Foundation, for example, has about $350MM AUM. The reason my friend told me about the foundation is that in their recent quarterly update, the foundation’s money managers sent the board a report entirely about investing in Africa. It turns out that the foundation is invested in African focused VCs and hedge funds.

I was pretty surprised that an obscure community foundation located in central New York was an LP in African focused venture funds. But it brought up an interesting principle. When traditional risk averse LPs are investing in venture capital, it should indicate that venture has become mainstream investing and forms a part of a diversified portfolio for a typical pension fund, endowment or foundation. In other words, traditional LP investments are a “trailing indicator.” These LPs are mainstream or even laggard on the curve of adoption as it applies to investors. When they invest in venture it is indicative of a trend that was innovative years ago finally being adopted into the “mainstream.”

On the lifecycle adoption curve of investment, some types of capital are trailing indicators. When confronted with a trailing indicator, the question is whether to innovate and drag the mainstream to you, find different sources of capital that understand you, or package yourself into an older more standard form that better fits the expectations of the mainstream and late adopters. That standard might be a great fit with investors, but a poor fit for the situation. Too often when fundraising, people think that money is money, that venture is the only capital source for startups, or that closed end 2 and 20 funds are the only capital structure for funds. Neither is true. In Africa, capital innovations are crucial, and copying mature capital markets and their investors’ requirements in the US, Europe, and China, are often a poor fit.

We’ve come to identify a variety of trailing indicators including where large scale capital pools invest, venture itself, philanthropic funded projects, and even venture studios. At Akili we’ve maintained flexibility in our investment strategy to take advantage of any capital structure or source that works for the ecosystem’s needs. But we’ve specifically structured Akili itself to be optimized for long term compounding growth in Africa. Our approach is designed for that purpose, and thus, there is always a tension between the innovation in how Akili operates, and in the conservative and trailing manner in which large scale capital organizes itself. We maintain the flexibility to take advantage of it, but do not try to twist ourselves into old models that are not fit for the unique challenge and opportunity we see. We intend to look forward, not look backward. To that end, recognizing trailing indicators is critical.

Verticalization

Recently, I spoke with a fantastic Nigerian entrepreneur with a precision agriculture seed company. He’s taken techniques he learned living in Holland growing seeds in greenhouses under extremely controlled conditions, to produce seeds with 10x+ yields. In establishing greenhouses and seed banking in Nigeria, he tried to convince farmers across the country to use his precision seeds, promising them yields they had never seen before. He was unsuccessful. They simply wouldn’t believe him. It was understandable. His response was twofold. First, he’s setting up a set of demonstration farms across Nigeria to prove his claims. Secondly, he’s setting up a farm management operation because he’s been asked by some of the larger commercial scale farmers to come in and manage their entire operation to prove he can increase their yields.

This is the story of doing business in Africa. In order to build one company, create one product, solve one problem, it is often necessary to build, create, or solve another. One of our projects is predicated on precisely this phenomenon. Early developers of minigrids (off grid energy systems typically powered by solar) across the continent did not account for a lack of actual demand from populations who never had access to electricity before (partly because they realized they could build the minigrids profitably with philanthropic capital). A few successful developers figured out that they needed to create their own anchor demand by creating other businesses that served the local community by consuming the electricity they produced. The project aimed to intermediate this process at scale in different communities through productive use centers which create anchor demand for minigrid energy. So for example, a developer in a fishing community built a warehouse with commercial ice making equipment. The fishermen didn’t need electricity so much as they needed ice, so that’s what the developers had to sell to them, while that business provide anchor demand for the minigrid’s electricity.

We often use the term “surface area” to describe the phenomenon whereby the more businesses we build, buy, and invest in, the more chances there are for us to identify adjacent problems or opportunities built on top of or in conjunction with existing growth and traction. This creates lower risk business building and cash generating opportunities, and happens organically rather than in a forced manner of searching for opportunities. But another way to see surface area, and building one business in conjunction with or on top of another to reinforce the value of both, is through the idea of verticalization.

From Japanese Keiretsu to Indian conglomerates to Chinese super apps, the idea of verticalization in emerging markets is fairly common, when solving one problem successfully leads to solving other problems when gaps in the market exist that prevent growth and scale. Verticalization is natural to fill in missing pieces of infrastructure, third party services, capital markets, supply chains, demand generation, and so on. While that verticalization is typically focused on one company accumulating large capital to solve related but different problems, eventually those should be handled by different companies with different capital structures that are designed for those problems.

Verticalization, or the navigation of adjacent problems vertically along a value chain, is a key principle that we employ across our portfolio to create synergistic, reinforcing growth from multiple dimensions, and help evolve the ecosystem itself in which that value chain exists.

Intermediation

One of the consequences of the lack of infrastructure and third party services across the continent is the lack of intermediation. The organizing glue between institutions, regulations, legal precedents, infrastructure, protocols, and local and regional political and organizational structures, is what silently allows you to easily open a bank account, buy a piece of property or a new home, or buy a business with the backing of government guaranteed loans. In Africa, without some of this organizing glue that is typically the result of institutional maturity, there is a significant need and opportunity for intermediation.

When incubating the idea for 54Carbon, what our partners and cofounders Kwaku and Kofi recognized from their long experience with government and foundation financing, was that large scale organizations with significant capital and mandates to create impact and change, rarely if ever have the ability to engage with or execute on a small scale, given the lack of that connective organizing glue. Climate related projects across the continent, for instance, rarely benefit individual smallholder farmers without significant intermediation, because private foundations and philanthropic organizations that sponsor these projects do not have the bandwidth or capabilities of working directly with such small entities, organizing and educating them, and managing them into collectives that can operationalize executable projects. The opportunity for intermediating organizations is precisely to act as an intermediaries between large scale capital sources and mission oriented institutions with large scale impact mandates, and the actual on the ground projects and individual farmers and local community stakeholders that stand to benefit from climate projects.

The story of development in Africa has often been one of large scale philanthropic and government capital trying to help individuals and small organizations but simply not being able to because of the lack of organizational and connective tissue. While the connective tissue of Africa continues to grow, the family of global capital sources that seek to shape African development: impact investors, foundations, DFIs, governmental entities, NGOs and other funders, will have to rely on intermediating organizations to make markets, build ecosystems, and organize individual projects, consumers, and businesses. In an effort to help bring that capital to Africa and operationalize it, Akili often looks at opportunities to intermediate and build some of that connective tissue. Opportunities for intermediation are vast, based on the virtually limitless possibilities of connecting people, places, and assets together.

In Closing

When observing trailing indicators, its prudent to evaluate whether existing capital structures are appropriate just because they are expected, or whether new ones are required that may take time, effort, and different stakeholders to successfully implement. When deciding on verticalization, its important to recognize that solving adjacent problems can be empowering and enabling, while requiring capital and resources that can drag down the business, and force a different set of economics that you will likely need an exit strategy for. Finally, intermediation is not only a principle, it’s an opportunity. When you see it out in the wild, a slice of missing connective tissue in the ecosystem, it can be used as a wedge to connect stakeholders, create value, and evolve a differentiated strategy.

When looking to do business on the continent, these are three principles to be aware of that have helped to shape our strategy. Hopefully they can inform yours as well.